Photographs by Joseph Johnston

Punch and Judy Show (edge of representation) is a new time-based installation piece I completed for the Bournemouth Emerging Arts Fringe as part of this years Arts by the Sea Festival. The work, which was shown at LUNG gallery on the 1st October, explores the conflict between systems of ordering and control, which Henri Lefebvre describes as ‘representations of space’, and visual representations of Bournemouth as ‘representational spaces’. 'Representations of space' are described as the maps, plans and strategies of urban planners and social engineers for controlling the way spaces are used and the people who use them, while ‘representational spaces’ are partly imagined, exist in the realm of the symbolic, and can represent of our hopes, dreams and identities. The work also seeks to embody the paradox of commercialised leisure: that however hard we try to escape the constraints of society and self, and predictability of everyday life, our attempts will always be thwarted by the organising systems and taken-for-granted typifications, which structure that which Zygmunt Bauman terms our 'life-world'; leaving us feeling disappointed and trapped. Moreover, the sense of subjective freedom we attain through everyday escape attempts, encompassing our ability to re-imagine and transform our surroundings, are also under threat from the tendancy to make our visual and discursive representations fall in line with a concensus or that which sociologist Erving Goffman refers to as ‘paramount reality'.

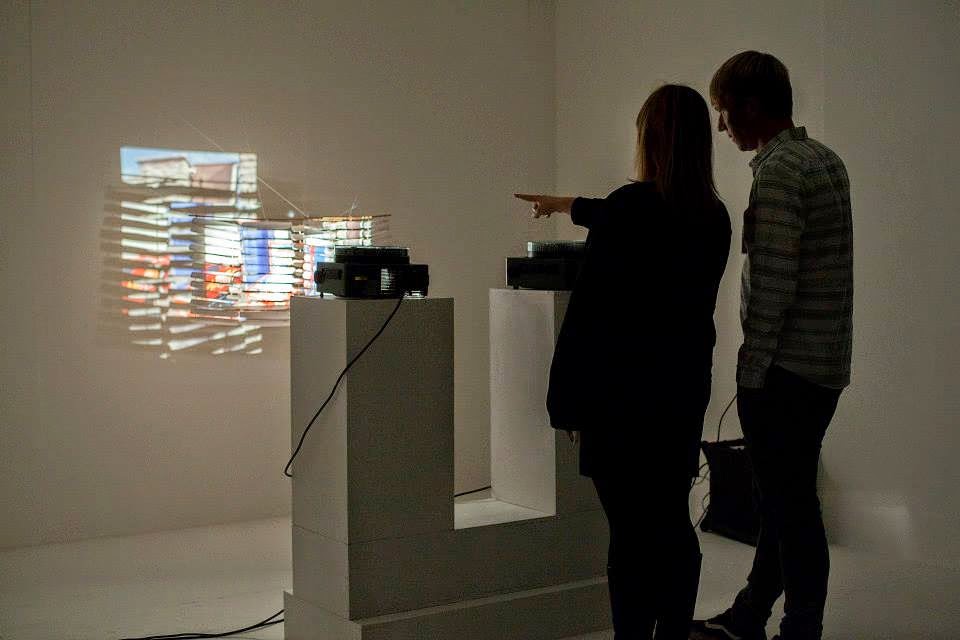

Punch and Judy Show (edge of representation) is a new time-based installation piece I completed for the Bournemouth Emerging Arts Fringe as part of this years Arts by the Sea Festival. The work, which was shown at LUNG gallery on the 1st October, explores the conflict between systems of ordering and control, which Henri Lefebvre describes as ‘representations of space’, and visual representations of Bournemouth as ‘representational spaces’. 'Representations of space' are described as the maps, plans and strategies of urban planners and social engineers for controlling the way spaces are used and the people who use them, while ‘representational spaces’ are partly imagined, exist in the realm of the symbolic, and can represent of our hopes, dreams and identities. The work also seeks to embody the paradox of commercialised leisure: that however hard we try to escape the constraints of society and self, and predictability of everyday life, our attempts will always be thwarted by the organising systems and taken-for-granted typifications, which structure that which Zygmunt Bauman terms our 'life-world'; leaving us feeling disappointed and trapped. Moreover, the sense of subjective freedom we attain through everyday escape attempts, encompassing our ability to re-imagine and transform our surroundings, are also under threat from the tendancy to make our visual and discursive representations fall in line with a concensus or that which sociologist Erving Goffman refers to as ‘paramount reality'.

The

piece is centred on two automated 35mm slide carousel projectors, set

slightly out of synch to suggest a clash or conflict of ideologies.

One carousel contains images of systems of ordering and control –

diversionary entertainments, maps, signs and information boards, CCTV

cameras and penalty warnings – and on the other houses visual

representations of Bournemouth as a heterotopia

of touristic

possibilities – moments of heightened aestheticisation

and improvised narratives in the visual vernacular of Continental

tourist travel. The first set of images (utilitarian), are taken

using Fuji film and have a slightly cold, detached feel, and the

second (romantic) are shot in Kodak to give them a nostalgic glow.

The

de-synchonisation of the carousels leads to a new set of image

combinations after each full rotation. This lends the work the element of chance as the sequence works its

way through

all potential variables of image juxtaposition. This is a direct reference to the carnivaleque strategy of chance as means of

eliminating the sense of boredom, pre-determination and fate experienced

in everyday life. The

use of outmoded analog

equipment

with

its mechanical action, together

with these chance juxtapositions, also suggest

both the fragility of life and the vulnerability of the meaning in

the autobiographical images we store in the

image magazines in our

minds (our own machines of representation). These meanings are also

enriched by the use of screens made from razor shells: the discarded

husks of lives once lived. The

work is backed by a specially commissioned soundtrack, made

in collaboration with Bournemouth

hauntological music

duo Language

Timothy! This

uses stereophonic

sound design to produce a sense of location: both inducing

feelings of disorientation and augmenting the dualistic visual

onslaught with a immersive sound-scape to overwhelm the senses. The

soundtrack is

comprised of field

recordings from a local

amusement arcade, together with a range of samples, including a 1950s

instrumental version of Stranger in Paradise; a title which is

perhaps the best metaphor for the tourist

paradox.